What my Dad's death has taught me about grief

Five years ago, my Dad died.

Whilst it was heart breaking, I truly believed because I had confronted his death, holding his hand whilst he took his last breath, that the hardest part was over.

One of the last things he told us was ‘it would kill me twice if you used my death as an excuse not to live your lives, use it as an inspiration,’ so I was utterly determined it would not define me. I was going to honour his legacy and go and live my life.

Within a year I went travelling for 6 months, had major knee surgery, broke up with my boyfriend who was my rock throughout Dad’s cancer, started a competitive new job, whilst convincing everyone (and myself) that life must go on and I was fine.

Turns out that was far from the truth.

Little did I know that all this positivity, drive and bravado were just coping mechanisms to mask the deep pain and hurt buried within me.

It wasn’t until a year later that my body forced me to stop. Pretty much overnight my existence became a crippling cocktail of panic attacks, self-doubt and an overwhelming feeling I was an inherently evil and bad person. Simple tasks like folding clothes were akin to climbing Mount Everest and the peaceful refuge of sleep descended into a prison of terror as I was forced to journey into the dark caves of my subconscious.

For what felt like an eternity I would lie in bed paralysed, sometimes shaking, in a sea of relentless and unforgiving emotions. When my friends and family would tell me ‘be kind to yourself you’ve been through so much’, all I could think was how pathetic I was crumbling at the first sign of real adversity.

I went to see a bereavement counsellor, but it only made me feel more insane as I tried to make sense of drowning in a raging ocean, through the lens of a terrified mind. I went to see a psychiatrist who diagnosed me as clinically depressed and insisted I take pills

It wasn’t until I found acupuncture that tiny cracks emerged in the darkness. It took time but eventually there was light again. No longer did I feel this was a great battle I must overcome. I slowly began to connect with who I was; that I’m by no means perfect but I am not the evil person my mind had constructed in its desperate attempt to maintain control.

I started to appreciate the simple things like cooking, going for a walk, sending silly memes and watching highbrow sitcoms like Friends again. I remember spending hours in the park playing with my dogs, soaking up the fact I could be outside without the noise of the planes reverberating shock waves through my whole body.

As treatment progressed, I felt a sense of clarity, power and peace I never even knew was possible. I realised on the other side of all this pain was so much beauty and possibility. That most of my suffering stemmed from attaching and identifying to the experience. That it was energy which needed to be felt and moved through me.

Looking back now I can see this was not just grief for my Dad, this was a lifetime of repressed emotions being unleashed. My body staged a crisis intervention so I could finally process and feel. It forced me to confront all the darker energies or traits within me, which somewhere down the line I’d internalised as negative. To accept that I am not just the positive and strong Georgie I had attached my identity to, but also incredibly vulnerable and fearful with the capacity to feel intense and contradictory emotions.

Four years on and I by no means am enlightened. Whereas before my grief was filed away in the ‘too painful to open’ cabinet, where I would dismiss my feelings and deflect the sympathetic eyes of friends with ‘it could be worse’, I now accept it is a part of me and am learning to embrace it.

I realise now you never get over grief, you just get used to its ebbs and flows as you navigate the continuous currents of life. As time goes by and the initial flurry of support gradually starts to drop off, you are forced to grasp the reality, permanence and ineffability of it all. The anniversaries, birthdays and huge milestones, whilst full of joy and happiness, carry a pervading sense of loss and sadness to them. His presence everywhere yet nowhere. It still astounds me how I can be running around happy as larry and a sudden smell, memory, or Dire Straits song can penetrate the depths of my soul and leave me choked with sadness. .

Even though all my defences still come out in full force when I feel the blade of grief about to strike, where I want to run for the hills and squash it away, I now have the tools to reassure myself that there’s nothing to be afraid of, it’s natural – that ‘this too shall pass.’ I allow myself to surrender to its weight and unapologetically wail like a wild creature for however long, safe in the knowledge that on the other side is clarity and in a strange way, a greater sense of connection to him.

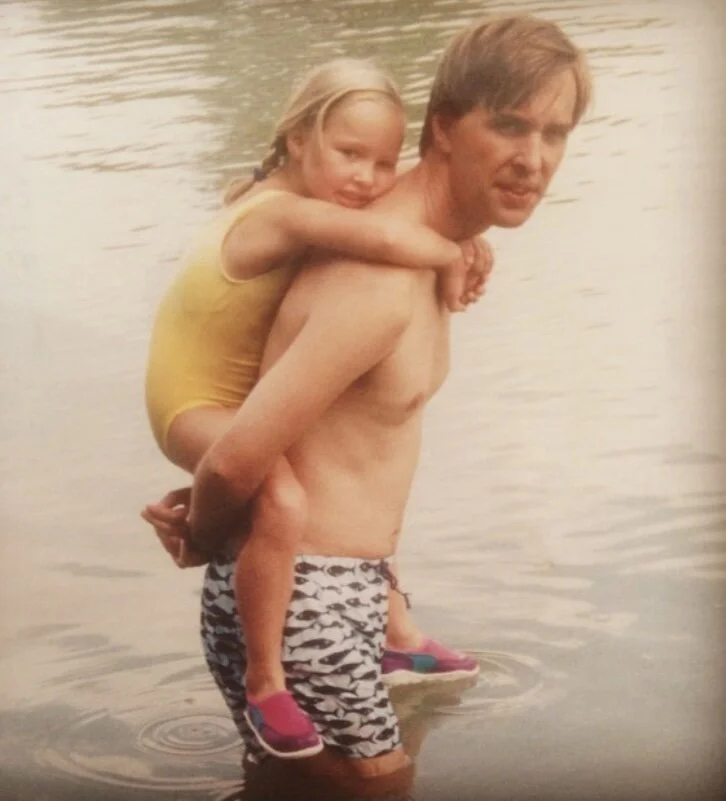

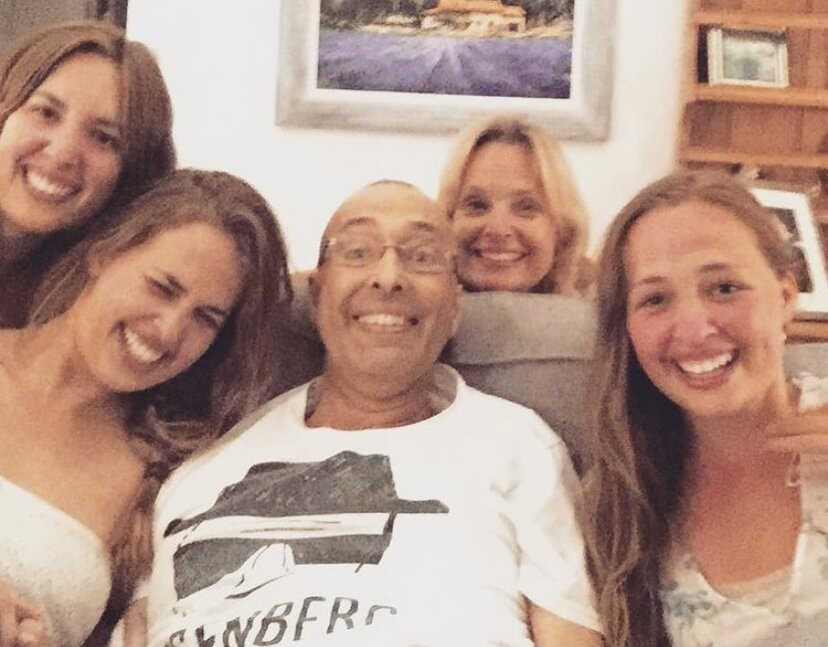

It’s easy to put someone you love who’s died on a pedestal. My Dad had his flaws, but mostly he was bloody brilliant. I would do anything to see his beaming grin and listen to his rubbish jokes, namely about his monstrous regiment of women he had to live with (my mum, sisters and I). I wish I could hear his opinion on the world from Brexit to lockdown, what he would have thought of acupuncture, to ask him how the feck do you run a business?

He had the most wonderful ability to cut through all the bullshit and see the bigger picture, empowering and leaving his presence on everyone who entered his orbit. He even confronted his death with utmost courage, accepting it as the natural course of his life, whilst still imparting his pearls of wisdom on us. He told us to always keep communicating because he knew we’d all process it in our own unique ways.

And he was right. Grief is completely unique and can take many forms for each person, however, what I do know is that you cannot outrun it or simply intellectualise it away. It is something you have to feel.

There is a wonderful quote in the book The Smell of Rain on Dust: Grief and Praise:

“Grief is praise because it is the natural way love honours what it misses…. If we do not praise whom we miss, we are ourselves in some way dead. So, grief and praise make us alive.”

It’s safe to say my interpretation of him telling us ‘ it would kill me twice if we used my death as an excuse not to live your lives, use it as an inspiration’ has evolved dramatically since five years ago. I realise now not living your life is actually to deny your reality and to ignore how you really feel. That to live life, is to accept and know that all those scary, painful and turbulent emotions have so much meaning in them when they are metabolised and transformed.

That there is always the promise of so much love and beauty through the journey of heartbreak and grief. That loss just like love is universal, boundless and, ultimately, teaches us what it is to be human and alive.